The early 20th century was a period of great discovery, and this included experimentation with new forms of art. In Paris, this led to Fauvism and Cubism, with both of these styles beginning to explore the elements of design for their own sake.

In Germany, the response was more introspective – with many artists seeking subjective inspiration in creating art, which art historian Paul Fetcher referred to as “the emotional experience in its most intense and concentrated formulation“. These artists used symbolic colour and linear distortion to express the “visual truth” of an inner life. Their artistic style became known as Expressionism.

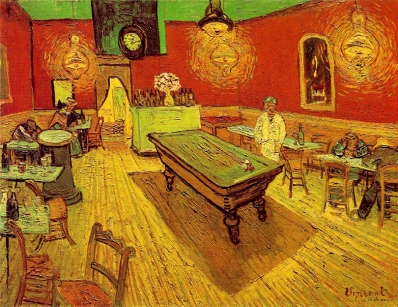

Van Gogh was a significant influence on Expressionism with his use of strong colour and brushstrokes, which express a real sense of emotion and tension.

Emergence of Expressionism – Die Brücke

In 1905, a group of artists known as Die Brücke (The Bridge) comprised Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel and Fritz Bleyl, who were architectural students in Dresden, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. They were joined by Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein and the Swiss artist Cuno Amiet in 1906, and by Otto Muller in 1910.

By late 1911, the principal artists of Die Brücke had moved from the relatively genteel city of Dresden to the teeming metropolis of Berlin, which by then was the third largest city in Europe, following London and Paris.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880 – 1938) was perhaps the most original and dynamic of the group – certainly the most prolific, creating over 2,400 prints, as well as paintings, water colours, tapestry designs and countless drawings.

More than any other artist in the group, he was aware of the innate capabilities of a particular medium, and worked consistently within its limitations.

As an artist, he was largely self taught. Initially interested in art nouveau, he visited museums where he studied old German masters and discovered the art of the South Seas and Africa. He was also influenced by van Gogh, Matisse (at that time a leader of Fauvism) and Edvard Munch. He sketched on the streets and evolved a rapid form of drawing – and by about 1911 he had perfected his own style.

Kirchner was highly productive until the outbreak of the war, and then again between 1917 – 1924.

He was self-centred and completely dedicated to his art. He had little regard for his subject matter as such, it was merely a framework to make visible his inner conception. However, his primary subjects were city life, street scenes, dancers and nudes.

Kirchner was enthralled by what he called “the symphony of the great city,” and responded to the intensity of the street life he found in Berlin by recording the urban spectacle around him.

In 1937, the year before his death, he wrote ” My goal was always to express emotion and experience with large form and simple colours, and it is my goal today… I wanted to express the richness and joy of living, to paint humanity at work and play in its reactions and inter-reactions, and to express love as well as hatred“.

Street Scenes

His renowned Street Scenes series, created between 1913 and 1915 in Berlin, is considered by many to be the highpoint of Kirchner’s career.

These scenes of city streets and nightlife, in particular the familiar presence of prostitutes, convey a characteristic feeling of Berlin prior to the war, which no other artist achieved.

Kirchner’s scenarios are theatrical – but they reflect the character of city. Women dressed in elaborate fur coats and hats with plumage are transformed by the green glow of a streetlamp. Black outlines, unusual colour palates, distorted figures, strong vertical lines and acute angles create atmosphere, energy and tension. In particular, note how well he uses small amounts of red so effectively in many of his works.

Unlike the other Street Scene paintings, where usual signs of city life are kept at the periphery, the monumental Potsdamer Platz (1914) is set in a recognisable spot in early 20th century Berlin—specifically Potsdamer Platz, as identified by the red train station and rounded building housing a café seen in the background. The primary figures of Potsdamer Platz, standing on a traffic island, are reminiscent of mannequins in store windows. (There is a photo of Potsdamer Platz in the Berlin photos above.)

Considering the large number of works on paper related to the Street Scene paintings, it is clear that Kirchner held high ambitions for this series. As well, the series includes drawings in ink, pastel, and charcoal, along with prints and sketchbook studies.

As he later said: “It seems as though the goal of my work has always been to dissolve myself completely into the sensations of the surroundings in order to then integrate this into a coherent painterly form.”

As part of his working process, Kirchner experimented with patterns of light and dark, combinations of colours, and various surface rhythms achieved through hatching pen strokes, gouges in woodblock, and scratches on etching plates.

In woodcuts, Five Cocottes (1914) and Women on Potsdamer Platz (1914), Kirchner seems to have closely followed the compositions of the related paintings. But there are significant differences, indicating that printmaking played an important role in Kirchner’s evolving imagery. His woodcuts were not translations of drawings into wood – for Kirchner the concept and the form of the print were closely welded, and the result developed organically as he was working.

Overall, it is Kirchner’s strong sense of the here and now, and his reflection of Berlin at that particular moment in history, that makes his work for this series so invaluable.

Later, when speaking of the Street Scenes, Kirchner said: “They originated…in one of the loneliest times of my life, during which an agonizing restlessness drove me out onto the streets day and night, which were filled with people and cars.”

Unfortunately Kirchner committed suicide in July 1938, when he became increasingly upset with the situation in Germany and the rise of the Nazis. Like many of his contemporaries, his work was denigrated as being degenerate, and all of his artwork in public museums was confiscated.

Sources Include: MoMA, Zigrosser, Carl; The Expressionists, A Survey of their Graphic Art, George Braziller, New York, 1957.

This blog is just a short excerpt from my art history e-course, Introduction to Modern European Art which is designed for adult learners and students of art history.

This interactive program covers the period from Romanticism right through to Abstract Art, with sections on the Bauhaus and School of Paris, key Paris exhibitions, both favourite and less well known artists and their work, and information about colour theory and key art terms. Lots of interesting stories, videos and opportunities to undertake exercises throughout the program.