ArtSeen

Malcolm Morley, Richard Artschwager, and Made in Vermont

New York

Hall Art FoundationMalcolm Morley, Richard Artschwager, and Made in Vermont

May 11 – December 1, 2019

Those who encounter the stellar parallel exhibitions by two unlikely friends, Malcolm Morley and Richard Artschwager, (Morley [1931–2018]; Artschwager [1923–2013]) at the Hall Art Foundation in Vermont, may wonder what deep affinity between them existed. Despite the differences in Morley’s and Artschwager’s stylistic and material approaches, their treatment of plastic representation, case by case explores issues of the phenomenology of perception, memory and displacement, birth and death, manmade and natural environments, the news, consumptive culture, and above all anxiety, destruction and violence. Each carved out a unique synthesis of image and object: both relentlessly and restlessly interrupted the conventions of art—be it subject matter or how an artwork should look according to its surrounding space and the times.

Both exhibits are organized chronologically. With Morley one detects first of all a fascination with war. The two earliest paintings depict the battleship HMS Hood (1964) and a profiled head of a young soldier surveilling the enemy with binoculars in Sub Watcher (1965); both are simple in their adherence of singular images and one-color grisaille palettes. During the decades of the 1970s and 1980s, the byproducts of the human conditions—whether inflicted by man or nature—became Morley’s predominant subjects, each materialized through various methods of execution from the artist’s broad painting repertoire. An outline of a menacing lion leaping half-way through the left of one canvas, painted ala Pollock’s drip technique on top of muted blue, chromatic fighting soldiers moving to the right in French Foreign Legionnaires Being Eaten by a Lion in the Sahara Desert (1986), is just as picturesque and inventive as the colliding scene of sailboats, ships, and combat planes with a sailor in the lower left gesturing his two flags as if he’s welcoming us, the viewer, to enjoy his particular theatre in Man Overboard (1994).

A massive highway crash from a bird’s eye view of various tractor-trailers, cars, trucks, and all types of vehicles crushed and piled on top each other in Theory of Catastrophe (2004) is just as terrifying and sublime as a single plane seen from behind and near eye level in Crash Landing (2010). The more recent painting, Medieval Divided Self (2016), reveals how an image materializes from a patchwork of signifiers: one might first guess it’s a self-portrait as a famous Cartesian mind/body split. The mirror image of the two large knights in armor readying a strike of their swords corresponds to two small knights on horseback preparing a joust with their lances, facing off on either side of the broken horizon. On the left a Viking ship on a high sea framed by a white picket fence perhaps suggests life as a journey; on the right a partial view of a town tucked lying behind the fortress wall, could be imagined as the artist’s birthplace. The sky on the right holds the same small knight (identical to the two below), paired with a falling plane on the left: both seem to provide a redistribution of images in repetition that can be redeployed at will and a gesture of practical mapping, as how objects in a child’s mind disregard time as a linear chronology and space as making “realistic” sense.

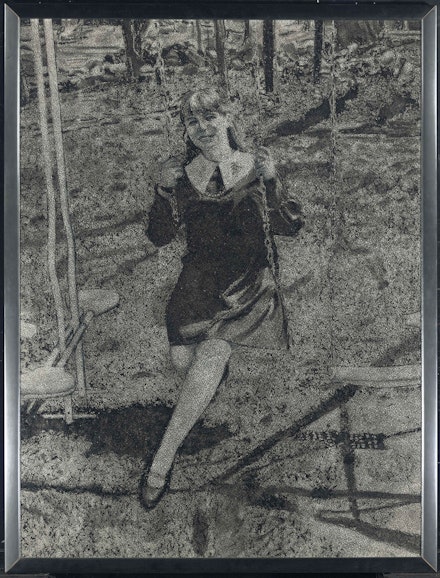

In the case of Artschwager, one notices how the artist mediates violence and destruction, birth and death, and everything else in between (often with a sense of the uncanny), through his depiction and activation of empty or negative space that resists iconic identification (which differentiates him from contemporaries such as Jasper Johns and Warhol). An early work, for example, Mirror (1964), is a framed mirror without a mirror. The “mirror” is an empty wall made of the Artschwager’s landmark Formica. The same can be said of Chest of Draw (1964), from which in addition to the non-existent drawers there appears in between the four legs the black Formica that constitutes the cast shadow of the empty space below. Untitled (Quotation Marks) (1980) is among the most metaphysical works, partly because it pays tribute to one of Artschwager’s most admired artists, Giorgio Morandi (who was once asked “why do you paint bottles?” to which he replied, “I don’t paint bottles. I only paint the space between them.”) Elsewhere, the notion of mystery is amplified by the object’s oscillations between description and evocation, facilitated by imagery that explores the limits of decipherable space. Women on Swing (Portrait of Ruth Dworken) (1969) is painted as a vigorous flurry of gradated black veils skating over the irregular celotex surface (similar to Georges Seurat’s black conté pulled across the upper ridges of laid paper. The unconventional surface resembles the materiality of mass-produced objects and “Do It Yourself” culture, as though a printed image had been excavated from termite infestation or the erosion of temperature and oxidation, contour lines are replaced by the sootiness and grittiness of edges; the synthesis of image and object is at once eerie and ambiguous.

These unlikely friends who shared overlapping interests and ambitions were both driven by an intense will to elude easy categorization. Morley, on the one hand, found refuge in psychoanalysis as providing equilibrium in his creative niche: while Donald Klein’s “massive separation anxiety” offered titanic energy and lent itself to the theatrical framework of Morley’s childlike wonderment of spirit, Freud’s “polymorphous perversity” (I prefer Morley’s rephrased “polymorphous infancy”) examined the early stage of an infant whose sense of touch is non-hierarchical. Artschwager, on the other hand, in the early 1960s—a few years after his furniture factory burned down—embraced everything he made with equal worth. Like a good doctor who treats all of his patients with proportionately appropriate care and attention Morley and Artschwager considered the making of their work as a scientific procedure. Through impersonally achieving the personal, everything they made became an art of generosity.

Also on view is an ongoing series Made in Vermont which displays recent works by local artists. Paintings, works on paper, and sculptures by Arista Alanis, Steve Budington, Clark Derbes, Jason Galligan-Baldwin, and Sarah Letteney together generate a symphonic experience through color, geometry, and bodies in action. They’re delightful in rapport with the two maestros.