In Memoriam

A Tribute to Malcolm Morley

Malcolm Morley In Remembrance

(1931 – 2018)

One tends to think of our artistic community, to some extent, as being similar to a symphony, which requires multitudes of instruments that each have their own distinct and unique sound, yet as a whole, they contribute to the total orchestration of musical experience. One can be certain that Malcolm is more like a violin or a piano rather than a viola or a celesta.

Anyone who has met or known Malcolm would offer a similar view, from up close the compelling details are deliciously visible, while from afar a broader perspective of the subject is generously revealed. As the saying goes, “there are those who read to remember and those who read to forget.” Malcolm, with great certainty, belongs to the former.

The following is our tribute composed by his friends and admirers.

Eric Fischl

I met Malcolm in 1976 when I visited his studio in NYC. The purpose of my visit was to invite him to lecture at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design where I was teaching. NSCAD at that time was profoundly and intransigently anti-painting and I thought that if anyone could change their minds about whether painting could still be radical or not, Malcolm was the one to do it.

At the time of my visit he was nearing completion of a painting about a train wreck, and as we stood there in front of it he explained his process to me. A friend had given him a shadow box with a model train smashed up and set against black velvet. He decided to paint it but rather than work from a gridded off photograph of it like he’d been doing, he decided to paint it from “life.” He floated a string grid of thread over the box and then cut cardboard to hide all but one square at a time. As if that wasn’t going to be difficult enough, he decided to paint it backwards. When he finished the painting he realized that no one would be able to tell that he had painted it backwards, and so he went back into it, adding the image of a crumpled Russian newspaper on top of the wreckage and then added a border with Japanese calligraphy on it. What didn’t occur to him until he’d finished it was that no one who didn’t speak Russian or Japanese would be able to tell that they were also painted backwards!

Anyone who knew Malcolm will have stories and memories not unlike this one. Every painting Malcolm created was a journey and an adventure. There was no one painting then or now who could make such a laden tradition feel like a novelty. There hasn’t been anyone who can match his child-like whimsy, wonder, and impish disregard for the weight and authority of painting’s own history. In his insistent deconstruction of the language of imagery and process of painting, with all its attendant clichés and sentimentality, he painted with an explosive energy that brought with it its own renewal.

Without Malcolm where do we go from here but carry on.

Andy Hall

I first became aware of Malcolm’s paintings at Charles Saatchi’s gallery in Boundary Road, London, in the 1980s. These bold, colorful canvases, full of unlikely and anachronistic juxtapositions, had a dreamlike quality with an unsettling hint of menace. They were hard to forget. Years later, as Christine and I became committed “collectors,” Malcolm’s work became a particular focus of our new obsession. We tracked down works that spanned his whole fifty-plus-year career as one of the most innovative painters of his generation. In the process we got to know Malcolm quite well and visited his Long Island studio on a number of occasions. That Malcolm, like us, was an émigré from England (he came from the same unglamorous suburbs of West London) probably resonated. But his deep understanding and knowledge of art history combined with a quick and mischievous wit was what really made our encounters a stimulating and memorable experience. On one occasion, we listened to Malcolm give a lecture about his work to MFA students at Yale. Malcolm had illustrated his talk with slides of some of his better-known works replete with the familiar Morley motifs including ships, model planes, toy soldiers, animals, motor cyclists and the like, all executed in his signature palette of bright saturated colors. At the end of his talk Malcolm answered questions posed by the students. The first came from a young lady who asked if Malcolm “had ever engaged the nude?” The then 80-year-old painter considered the question for a moment, narrowed his eyes and dead panned: “Yes, on many occasions.”

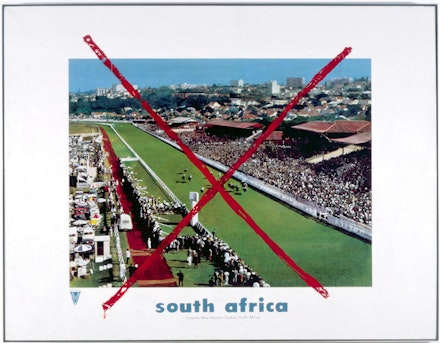

From his early days in New York, Malcolm befriended and hung out with other artists. It was Richard Artschwager who told him to quit experimenting with sculpture and stick to painting ships. Supposedly Malcolm, following this advice, lugged his easel down to Chelsea piers and tried to paint the ocean liners that were docked there. He eventually gave up in frustration finding it impossible to fit the huge vessels on his canvas at such close quarters. Instead he bought some post cards of these passenger liners from a nearby newsstand and in his studio faithfully replicated the cheap four color printed images onto his canvases by using a grid. Thus was born his signature style and method along with a genre of painting dubbed “photorealism,” as well as some early Morley masterpieces like SS Amsterdam in Front of Rotterdam and Cristoforo Colombo. But Malcolm soon rebelled against being pigeonholed in this way. He defaced one of his paintings—a copy of a South African tourist brochure of a horse racing track (the aptly titled Race Track)—with a large red “X” the day before it was to be photographed for an article about him in Time magazine. Thereafter he progressively subverted his own earlier works. His imagery became more and more gestural to the point where by the early 1980s he was considered a leader of the neo-expressionist wave. How many painters can be categorized as both a photo-realist and a neo-expressionist? Subsequently, Malcolm successively synthesized these two polar extremes by painting gridded arrays of pure gestural abstraction that at a distance resolve into photographic imagery (or as he preferred to call it) “super” realism.

About 10 years ago we were chatting to Malcolm at a dinner honoring him and some other New York based artists—including a very well-known one with a famously large Manhattan studio and dozens of painter-assistants. Malcolm motioned in this artist’s direction and mentioned that he had recently spotted a help-wanted ad in the newspaper seeking “photo-realist” painters. He called the number and asked what they were paying. Malcolm wasn’t too impressed with the rate and said he thought it should be more. He was asked if he “could do photorealism?” to which Malcom answered breezily, “oh yes, I invented it.” We are going to miss you Malcolm.

Robert Storr

A Working-Class Dandy is Something to Be

Some memories spring into focus with the unimpeachable clarity of first-hand experience and others flicker around the edges of such clarity in such a manner as to suggest that they aren’t really one’s own recollections but rather variable mental reconstructions of things one has heard, things that however second hand nonetheless made so deep an impression that they feel first hand, earned. Years ago, when I was teaching at the Studio School on Eighth Street, I seem to recall having crossed Washington Square and noticing a man intently making $10 sketch portraits on a French easel of any and all comers.

It was the mid-Eighties and the man was Malcolm Morley at that time riding the crest of his second big wave of art world fame as an emblematic elder statesman of what the Royal Academy called A New Spirit in Painting. Such was the title of the RA’s 1981 survey show of post minimalism and new media art. In 1984 he was chosen the first winner of the newly inaugurated Turner Prize, further confirming his status as a pivotal talent in the eclipse of the former avant-gardes of the 1960s and 1970s, all the while being emblematic of some of them, most notably the advent of photo-mechanically based practices that would morph into “anti-aesthetic” Post-modernist “discourses” of the 1980s. An expatriate Brit who brought his working-class accent and a pugnacious style with him from the rougher parts of London where he grew up during the Blitz as well as an avid enthusiast of early aeronautical exploits, Malcolm was the Wrong Way Corrigan of Photorealism who became famous for his anti-expressive renditions of luxury liners, contemporary interiors, race tracks and other “pop” culture subjects. By the 1980s all this had morphed into vivid, deceptively awkward renditions of toy soldiers and other tokens of boyish fantasy that could not be more pronounced, reminding one of Picasso’s statement that having been well trained in traditional skills it had taken him years to learn how to draw like a child.

This transformation, as well as his academic training and official honors, speak to Malcolm’s dedication to workman-like craft—as a practitioner of a medium that was officially dead he took the greatest pleasure in declaring his devotion to “the fine art of oil painting”—in constant dialectical tension with his utterly unpredictable playfulness which, Borstal boy that he had been before he found art, drove him to seek out and study rules the better to break them. For me the excitement of looking at his work overall and still more so example-by-example, was watching the tug of war between his drive to dazzle like the old masters and his impulsive need to mess with the viewer’s expectations—and his own.

Early in my tenure as a Curator of Painting and Sculpture at MoMA, and less than a decade after A New Spirit in Painting, I had occasion to acquire a looming, brushy painting of a fishing tub Michelle (1992) and, later, as Dean of the Yale School of Art, I organized a compact retrospective of Malcolm’s work. At Yale the one gallery synopsis of his career began with a conservative Euston Road-type landscape made while he was a student (the motif was the studio/residence of Sir Joshua Reynolds which was then inhabited by the British actor John Mills who came out to check on the person camped on the green outside his house and bought the work on the spot)—to brand new installation works incorporating the façades of pubs and other talismans of his childhood.

When I initially broached the issue of exhibiting his work Malcolm had just come through a life-threatening illness and seemed rather fragile. However, except for the Brooklyn Museum which mounted a Morley survey in 1982, the major New York institutions had generally neglected him, and thus despite his vulnerability—or perhaps because of it—Malcolm was anxious to take these 3D paintings public. I was, too. (In 2013 I organized a similar capsule retrospective for Alex Katz in the same space for the same reason.) And so, the Yale School of Art showed them for the first time as the climax of a synoptic account of his career that began with the landscape mentioned above and encompassed major Photorealist canvases, funky painterly montages and reliefs of the 1980s, watercolors and more, many of which featured his preferred boy’s toys—akin to those of Chris Burden, prompting one to wonder what a Morley/Burden exhibition might look like and what insights into “masculinity” it might offer—model planes, model boats, toy soldiers, and wonderfully polychrome sculptural animals wild and domestic, as well as a life-sized figure of a British marine. In the aggregate, they demonstrated a lifetime of empirical invention in many media and many representational idioms.

For students hamstrung by the ideological strictures of post-modern discourses of numerous kinds Malcolm’s object lessons in full-bore multifarious facture were liberating. They provided abundant evidence that insouciant improvisation, betting on the long shot and choosing aesthetic anarchy over decorum could bear spectacular results—so long as they found themselves at the disposal of fearless and ceaselessly tinkering hands. A graduate of the school of hard knocks—in addition to reform school Malcolm did time in prison for burglary—and of the Camberwell College of Arts in the then unglamorous South London along with the tonier and more prestigious Royal College of Art nearer the center of the city, Malcolm was an insatiable student of the Grand Tradition, whose late life passion for “swagger portraits” of Admiral Nelson and other “heroes” of the British Empire would have cast him as an easy target for post-colonial critique had his obvious, not to mention fertile, contradictions and irrepressible contrariness not made him so engaging.

Moreover, Malcolm wore those contradictions like badges of honor. Or rather like a costume in his own updated re-creation of the charming shit-stirrer Gulley Jimson from The Horse’s Mouth. Accordingly, Malcolm arrived at the opening of his exhibition at Yale wearing an elegant felt hat and a hyper-posh black woolen overcoat from Saville Row, which he peeled off to reveal a fire engine red plaid suit set off by a bright green tie. Then, having made his entrance, he worked the room for several hours, talking to students and faculty not like an elder statesman resting on his laurels but like the restless, trouble-making maker that he was, someone who could give the youngest of the young and the cheekiest of the cheeky a run for their money. The gallery was abuzz with his images and with the effect that he had on all who came in contact with them and with him. It was a great evening. The paintings remain and they will continue to startle the eye and stimulate conversation long after the “verities” of late 20th and early 21st century critical chatter have been rendered obsolete.

Robert Storr

Brooklyn, 2018

Richard Serra

Looking at Malcolm’s paintings

What it is

Is and is not

What it means

When I look at Malcolm’s paintings I mix my sensations and memories with my immediate perceptions. I don’t know how to separate them, I don’t understand what comes from my recollection and what comes from my perception.

Malcolm’s paintings converge with my memories even though their subject is Malcolm’s memories, Malcolm’s sensations.

What you see and what you think you see are not always synonymous with what’s present which also includes what’s absent; what’s in the gap, the caesura of perception.

In that gap I find cynicism that targets social progress, I find friction, collision, collapse and catastrophe.

The difference between one Morley and another is in the ideas they contain about painting which take me beyond the visual.

Richard Serra

February 2005

Dorothea Rockburne

Dear, sweet Malcolm,

Damn! You know that I love you, love your sheer devilment! I’ll miss you, your art, and your ever inventive, wonderful intelligence.

We met in the early 70s on Crosby Street. You were painting a street scene from your fire escape. Spotting me you introduced yourself. Showing me your work, you explained that you painted upside-down. That didn’t get a rise from me. You continued to chat it up telling me how you learned to paint… in prison. [Still no desired effect from me.] How could you know I was partly English? I was raised in this rapport!

Next, you explained in England you had been a second story man, a thief. You related how you would enter a bedroom through the open window. Couples were either sleeping or fucking. You’d emulate their breathing, go through their pockets, then escape. Caught and sent to prison you learned to paint and fell in love with art. Only now can I tell you how amazed I was by your past, back then I simply nodded and said hmmm!

The next hilarious Malcolm scene occurred when we were both in Xavier Fourcade Gallery in the 80’s. Xavier had, against all odds, managed to clean up your bad habits. That freed you to paint. You were doing well.

The summer of 1981 was hot in New York. I was working on the Large Angel Watercolor on Vellum Series. Xavier and I were having fun with Angelology. On the phone daily from Bellport, he would translate archaic angelic information for me from his French Library; often he would send a car on Sundays to drive me out to Bellport for a welcome swim and lunch.

On one such occasion, Malcolm and his then new Brazilian wife joined us. We were sitting at the table dawdling after lunch when Xavier suggested a game: If we were to die and be reincarnated as an animal, which animal would each like to be and why? I was breathless waiting for your response. The question went around the table with the usual answers—a giraffe, a lion, a bear, a cat, a dog, a tiger etc. until it came to you. Carefully studying everyone’s face you stated (having just been married), “I would like to return as a woman.” Silence reigned. It worked. They were shocked and I broke up in laughter. We had always loved and understood each other.

Your social form of rebellious love will always remain in my heart.

Love,

Dorothea

Bonnie Clearwater

Malcolm Morley was a risk-taker. Pigeonholed as a photorealist early in his career (a term he rejected in favor of “super-realism”), Morley defied categorization by frequently changing his work. As soon as a body of work was successful, he felt compelled to take a new tack, remarking, “You only really succeed by taking risks.” A child of war-time London, Morley lost his unfinished miniature model of the battleship HMS Nelson when he left it to dry on his kitchen windowsill, only to be destroyed that night, along with part of his home, in the blitz. This model became his “Rosebud,” representing the perfection he sought to achieve throughout his career. The frequent changes in his work perplexed those who wished he kept making the exquisite paintings of photographs of ocean liners that brought him fame in the 1960s, but his bold experiments were hailed by other painters. In 2005, when I was organizing back-to-back solo museum exhibitions for Albert Oehlen and Morley, Oehlen told me that Morley was the American artist who had influenced him the most. Although I never asked Oehlen what he meant, his revelation propelled me to remap Morley’s work as a missing link between a vein of modernism that fused abstraction with figuration, and the artists of the postmodern generation. Painting gave Morley a sense of peace. Dividing his source imagery into square sections on his canvas, his world became whichever quadrant he was painting at the moment. His technique was democratic, no square was more important than the other. And when he reached the last square, all the segments coalesced into a single brilliant image. I was fortunate to work with Morley when he was 74, and at the top of his form. By then he had the luxury of time to understand the consequences of his actions and to find meaning and continuity in his work, as well as his place in art history.

Bonnie Clearwater

2018

Alanna Heiss

Malcolm was a rascal. No doubt about it. He was also a tormented, talented, ambitious visionary. He was dangerous. Primarily self educated, he was a voracious reader and wildly over informed about a vast array of subjects. His wit was quick and sharp and could be deadly. I was always quite careful around Malcolm even when joking as I wanted to avoid exposing a lack of knowledge. I wanted him to respect and like me.

I succeeded, largely, in this goal. Malcolm frequently, and generously, referred to the importance of a show of his work that I organized at the Clocktower in the ‘80s.

I believe it was Klaus Kertess but it could've been any one of a number of (painter) friends who alerted me that Malcolm both needed and deserved a show at the strange, exclusive, tower in the sky that I ran where I exercised the extraordinary luxury of curating one artist shows in a space high above the Tribeca skyline with a large clock on each side symbolizing both timelessness and timeliness. Called the Clocktower, there had been since 1972 a run of wonderful shows each focusing on the special and sometimes strange quality of artists’ dreams. This is where Carl Andre showed the poetry he wrote for his mother. This is where Dennis Oppenheim did the famous piece with the German shepherd. This is where Lynda Benglis first made her odd tied gelatinous bows, and this is where I invited Malcolm to develop a show that would explain to his artist colleagues what he had been up to the previous five years.

We all knew Malcolm was a great artist, but we also knew Malcolm was troubled and from time to time he would reject all around him, including his own work. He explained to me that he wanted this show to not only prove a point but to prove several points, his position in painting, and his opinion about other painters. Always optimistic, I suggested that we organize a panel with three other painters he admired to discuss their positions. The painters we chose were Brice Marden, Robert Ryman, and Joan Mitchell. Knowing that Malcolm was held in high regard, I thought that support from the great painters of the moment would increase Malcolm’s confidence that he could follow his own path. Unfortunately all the painters rejected this invitation. Brice told me he was too depressed to take part in the exercise. Joan Mitchell told me to get lost, and Robert Ryman said he couldn’t speak in public. I made Ryman come because he is such a nice guy that he couldn't resist but true to his promise, he refused to say anything about painting except “uhm. Uhm uhm.”

Malcolm and I had chosen a beautiful show of powerful new paintings which accurately reflected his previous years of unseen work. The opening was mobbed by artists excited by the opportunity to see the new work and to hear Malcolm explain his role as a painter in the cluster of the admired painters of the moment. I was proud to be a part of the evening and to hear Malcolm speak with his customary extraordinary abilities. The panel began and I introduced Ryman and Morley, and when I asked Morley to speak he dived under the table and brought out a large paper bag from which he gleefully extracted handfuls of torn up paper that he threw in the air! He then ran around the room throwing the paper in the air yelling, “that’s all there is folks! That's all there is! You can just tear up all your theories and throw them in the air, it doesn't mean anything!”

Although this was the time when performance was emerging as a viable exponent of art logic, this performance failed miserably. Once again Malcolm was seen as a kind of discontent who put little value on that which we valued so highly.

However the show itself was the argument and the only argument needed for Malcolm’s genius despite his deliberate rejection of the opportunity to be a member of the club. It was clear and although Malcolm was no club member and would never be, he was a real artist.

Les Levine was worried that Malcolm was a potential suicide. He told Malcolm, “if you think you might do it, be sure to call me and I’ll come and take a last picture of you.” That’s how he came to take a picture of Malcolm in Central Park sitting disconsolately on a bench. We used that photograph, of a lonely and sad Malcolm for the poster of the show.

Peter Krashes

Malcolm liked a perhaps apocryphal story about a conflict between Alexander Calder and Frank Lloyd Wright. In Malcolm’s telling, Wright was forced to accept a Calder mobile in the atrium of the Guggenheim so he stipulated it be solid gold. Calder assented as long as the gold was painted black. Malcolm saw gamesmanship as a natural outcome of creative convictions. He called it “historic ambition.” He took on his own actions as well as figures like Picasso and Cézanne and Turner who loomed large in his creative life.

I think the bold suits Malcolm wore in public, and the hand-striped overalls he wore in the studio were a product of his deep self-identification with being an artist, and more specifically with painting as a practice. He wore and painted the same colors. At varying points in his career he performed as a painter in public and created surrogates for himself inside his work. I don’t think he believed there should be much separation between his dream-life, what happens in the studio, and life in public. This lack of boundaries produced uncontrolled outcomes, (he painted phalluses while collecting containers in the studio—we called it “The Search for the Perfect Container”) and startlingly fine-tuned insights. It also enabled him to set aside his own inhibitions, whether with brush or career. It was good if an action evoked opposition, especially his own.

As vivid as his imagination was, his painting was nearly always grounded in observation. Not just his painting. He always looked around for better ways to do things. If a tool he needed didn’t exist, he made it. Perhaps the single tool he made that best captures him was a pair of gridded eyeglasses. They help break down what you are looking at as long as you don’t move. Malcolm was generally on the move.

Sir Norman Rosenthal

As I write this short tribute to the memory of one of the greatest painters of the last half-century, Malcolm Morley, I happen by chance to be sitting in the middle of an outstanding group of his works belonging to Andy and Christine Hall. The Halls, particularly independently-minded collectors, were great friends and supporters of Morley since the nineties. This group of paintings is housed in Schloss Derneburg, near Hanover in Germany, formerly occupied for many years as a studio by Georg Baselitz, but now brilliantly transformed by the Halls into a museum accessible to visitors—a place also of true romance.

This coincidence means much to me personally, as Malcolm was the poster artist for what was by far the most significant art show I ever co-curated, A New Spirit in Painting, which opened at the Royal Academy of Arts in January 1981. I collaborated on A New Spirit with Christos M. Joachimides, who too passed away earlier this year, and Nicholas Serota who went on to stage a great show of Malcolm’s works at the Whitechapel Art Gallery where he was then director.

In the early 1980s, Malcolm was making those extraordinarily dense expressive paintings of parrots, camels, cowboys, and native Americans that evoked exotic, even lost “fantasy” child-like colonial worlds. They matched, nonetheless with their very own style and mood, the new painterly expressionism of his European contemporaries, such as Baselitz himself, as well as newer, younger artists on the scene, such as Julian Schnabel and Francesco Clemente. But the fact is that Malcolm had much earlier already led the world of new painting by literally inventing Hyper-Realism, largely in a great series of ocean liner paintings, which in their time served as a great antidote to Pop Art while at the same time being a kind of necessary and vital sub plot to that world.

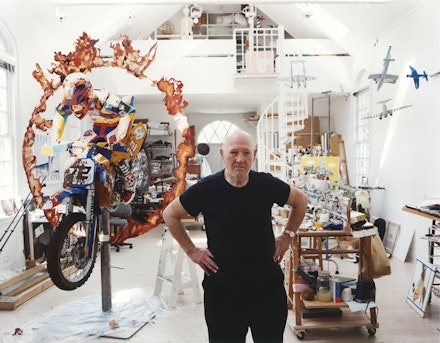

Malcolm was, of course, born into a British working-class family, but became a quintessential great American painter. His style of painting was constantly evolving as it conjured various motorized sports vehicles—bikes and cars, airplanes, but also horses. But with the evolution Malcolm always conveyed the profundity and even necessity of holding onto a certain child-like innocence. He was, indeed, immensely widely read, especially in matters pertaining to the human mind. However, it is touching, at least to me, that his last paintings present us with richly colored fantastical worlds of medieval castles: the knights that joust in shining armour were all based on toys that littered his house and studio. And yet through it all Malcolm was the most modern of painters, not say of individuals.

Malcolm was a marvelous man indeed, one of huge artistic achievement against many odds!

Derneburg

July 2018

Nancy Hoffman

It has been many years since I have seen Malcolm, and while we lost the thread of connection, he was never far from my mind—especially his energy. I marveled at his willingness to go out on a limb and stay there, allowing in dream-like images, which became part of his work. His daring was undeniable, his mash up of subjects was uniquely his. He was not a “photo realist” like others in that movement, though he often used postcards and photos as reference.

He was a renegade presence in SoHo in the ’70s and ’80s, peripatetic in his connection to galleries. Nancy Hoffman Gallery had the good fortune of working with him during a particularly fertile, rich, adventuresome period of his life in the ’70s when he was experimenting with wide ranging imagery.

In the summer of ’78, while at the Venice Biennale, I came upon his spectacular L.A. Phone Book page painting, real yet raw, pulsing with life. I decided to send him a postcard to tell him that he stole the show, and plucked a card of Guardi's Bucintoro from a postcard vendor, never thinking it would turn in to a painting. Lo and behold, months later Malcolm completed The Ultimate Anxiety with Guardi's image painted in his muscular fashion, and through the center of the painting he placed a toy train from the Lewis catalogue, recalling his London youth, referencing the shape of Venice bridges and disrupting what would otherwise have been a classic image of the ship that protected Venice.

That was Malcolm then, the brilliant disrupter. He and his genius will be sorely missed.

Nancy Hoffman

Brooks Adams

Malcolm Morley needed me in the ’90s. That is, he needed a younger American critic to write an essay for his 1995 retrospective at Fundación “la Caixa” in Madrid, organized by the European poet, curator, and former museum director Enrique Juncosa. All the subsequent catalogue essays for galleries were a terrific chance. Do you know how exciting it is to get a first crack at deciphering dense new paintings, and the occasional sculpture, by an eccentric, quixotic genius?

In person, during our studio visits, Malcolm was often flirty and gallant, lacing his comments with the occasional “dear” or “darling.” What did it signify? It seemed a throwback to an older, English lingua franca of difference—a strange survival in his now more established, though still quirky, individual style of speaking.

In the late ’50s and ’60s, was he an Angry Young Man or more of a Joe Orton type? There was that criminal, Jean Genet-esque aspect of his youth. Was he a bohemian tough, like one of those scrappy, Fitzrovian artist-pickers and their hangers-on in Anthony Powell’s multi-volume novel, A Dance to the Music of Time?

New York, February 2011. It was cold. I was staying in a hotel on the Upper East Side, took a cab to Penn Station, then a train to Bellport where Malcolm met me at the station, seemingly still in his pajamas, an overcoat thrown over them. I had come from Europe as he had, long ago. The conversation in the car was polite. He was reading a biography of J.D. Salinger, a strange choice I thought at the time. We were floating through the winter landscape of Long Island. I realized with some shock that Malcolm was driving and that I was going to be spending the night at his house.

Brookhaven. July 4th weekend, 2018. Around the pool at Tom Cashin and Jay Johnson’s, down the road from where Malcolm had lived and worked in a converted church, Lida Morley mentioned that Malcolm was once a redhead.

Greece, July 2018. It was hot. I was sitting in the Pirate Bar in Hydra, looking at the boats. One with an electric blue stripe on a red hull. Another caique painted a dull dark blue with a feeble yellow stripe. The white crests of water from speedboats, wakes crisscrossing, when we had earlier arrived by ferry from Metochi: all of it was Malcolm.

Gian Enzo Sperone

Dear Malcolm,

For many years I’ve been unable to classify your painting: fathers, mothers, grandparents, etc.

It isn’t that I haven’t tried. The thing is, you were—and are—an unusual painter whose originality doesn’t reveal any underlying influence.

One of my obsessions in my youth was the problem of influences in art. That subsided in the early ’70s with Harold Bloom’s book, The Anxiety of Influence, but it does explain why I’ve always found your work mysterious and undefinable; precisely because it’s rather rootless.

Your work isn’t this and isn’t that, doesn’t derive from this and doesn’t derive from that, respects the norms but at the same time violates them: consequently, it forms a page of true independence and extravagance in the history of painting.

In a context punctuated with the triviality of phoney and often unimaginative anarchists, your intuitions—yours and yours alone—are prized material.

Your friend and dealer

Gian Enzo Sperone

Ken Miller

I first met Malcolm Morley at one of Alanna Heiss and Fred Sherman’s famous summer paella parties. Malcolm was probably already in his seventies, I, headed in his chronological direction. Sitting down over plates of delicious rice, beans, shrimp, and clams, lovingly prepared by Alanna's paella specialist, Charley Balsamo, we bonded over a mutual life-long love of marijuana. I sensed that Malcolm’s wife Lida was becoming increasingly nervous as the conversation lingered on that subject, and then it reached the point where he asked with a gleam in his eye “Are you holding?” My wife, Lybess, pinched me and nodded her head in the direction of Lida who was frantically waving me off.

We subsequently met many times at their studio/home in Brookhaven and at ours on 17th Street in Manhattan where hangs a particularly nice Morley, an ocean liner with a life-boat dangling off its side. There's a lamp strategically placed so as not to obstruct the view but to protect the escape vessel from hands which might carelessly knock it from its moorings.

Once he admired a Moroccan fez I had donned on a lark, and after I took it off right then and gave it to him, it remained on his head for days, the white on his rice. The conversations we have had about art, philosophy, human nature, and our pasts—often punctuated by laughter—resonate as some of the more honest and essentially human exchanges it’s been my privilege to experience.

Requiescat In Pace, Malcolm. Juvenile delinquent. Borstal boy. Bricklayer. Three dimensional artist. Multidimensional man. Truthspeaker. Deepseer. Lifelover. Friend.

Ken Miller

Enrique Juncosa

I met Malcolm Morley as I curated a retrospective of his work for Fundación “la Caixa” in Madrid. The show opened towards the end of 1995 and travelled the following year to the Astrup Fearnley Museet voor Moderne Kunst in Oslo. Malcolm was a great person to work with: he was an enthusiast, incredibly bright, and had a terrific sense of humor. He was also very generous. I was a freelance curator at the time and had not organized that many shows yet, but he seemed happy with anything I suggested or wanted to do. He also loved to talk, from old time stories and gossip about the art world, to serious reflections about his art and that of other artists he admired, like Picasso or Cézanne. He talked about painting as if it was a matter of life and death. He also liked to travel, especially by ship. He loved boats and aeroplanes—their shapes but also their suggestion of adventure. I remember Malcolm enjoyed meeting an admiral, who for some reason attended his opening in Madrid. He did my portrait while we were having a drink in the terrace of a bar, and later gave me a wonderful watercolor depicting a waterfall in Jamaica. When we were in Oslo, everything was covered with snow and it was freezing. We had dinner in one of the houses of Mr. Fearnley. He had a room furnished with Viking furniture, and also an indoor swimming pool and a ping-pong table. Malcolm was very good at this game. Mr. Fearnley also enjoyed big game hunting and there were heads of large antelopes hanging all over the walls. Later on, I bought one of Malcolm’s paintings for the collection of the Museo Reina Sofía. Later on I visited Malcolm and Lida at Bellport. It really suited him to live by the sea. Malcolm’s work is greatly admired by other painters, and I remember having spoken about him with Terry Winters, Cecily Brown, Miquel Barceló, Francesco Clemente or Philip Taaffe. Morley’s work was central to the art debates that dominated the art world in the ’70s and ’80s. After that, his work became more and more personal, like perfect material for psychoanalysis. It would be great to see his work in depth in New York very soon.

Robert Hobbs

Pre-Imaging and Painting Discrete Bits of the Visual Spectrum

Unlike other Brooklyn Rail contributors offering telling anecdotes about their friendship with Malcolm Morley, my association with him was strictly professional. In 2004 Angela Westwater invited me to write an essay on Morley for a May 2005 exhibition of his work at Sperone Westwater. I then spent an afternoon with Morley, who had been profoundly affected by a breakdown several years earlier that had left him speechless for six months, resulting in a return to his 1960s super-realist painting practice. This episode no doubt made him regard each interview as an opportunity to set the record straight about his ongoing effort to pre-image a single cell in a gridded photograph in order to transform it into painterly equivalents, and he was consequently very forthcoming.

Morley felt the need to be as faithful as possible to the discrete, small cutout blocks of photographic imagery that he would take from a chosen photograph in order to carefully analyze each one in an attempt to pre-image it in terms of the tones he would then transpose to his canvas. Even after undertaking these precautions to ensure painting a primary role in the conceptualization and actual production of individual cells, he realized that slight, yet critical, qualitative gaps or breaks would intervene.

Although this process has often been attributed to Chuck Close’s efforts to break down photographic images into discrete bits of visual information, Morley started doing it two years before Close, who was one of his fellow teachers at the New York School of Visual Arts. Even though Morley worked with photographs, he was far less interested in analyzing photography’s ways of warping vision through the necessary licenses it takes with depth of field than in understanding how he as an artist was able to perceive the world. For all their drama—and certainly Morley’s subjects of sports and news events in his later works are highly dramatic—his own acts of pre-imaging, followed by his transposition in paint of the resulting images, is the very human stage comprising his stirring paintings.

In my opinion Morley’s approach has definite antecedents in the English picturesque tradition of envisioning actual landscapes as equivalent to works of art before actually painting them. His tactic also resonates with Cézanne’s heroic efforts to understand a selected motif in nature before transposing it to watercolor and oil paint. I view Morley’s pre-imaging as an acceptance of Kant’s a priori that precludes any direct understanding of the world since it is always mediated in terms of space, time, and the causes one might attribute to it; but Morley does so while still countering this transcendental means of knowing through the most rigorous empirical means possible.